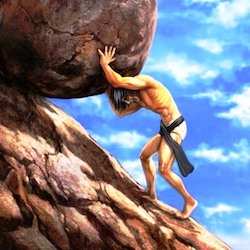

In Greek mythology, Sisyphus was condemned to ceaselessly roll a giant stone to the summit, only for it to roll back down of its own weight. In trying to fix health care, we Americans are like Sisyphus. Bearing witness to the strenuous futility is exhausting.

First, let’s take a look back to see how our health care system evolved. Every U.S. president throughout the 20th century had universal health care high on his agenda.

— In the early 1900s, doctors organized to create the American Medical Association. Policy-makers bow to this deep-pocketed group that has a long tradition of killing legislation that changes health care. Unless the AMA is on board, health legislation is pretty much doomed.

— In 1912, Theodore Roosevelt attempted mandatory health insurance, but the effort was sidelined by World War I.

— First fundamental change: In the 1920s, the cost of health care increased relative to other sectors, and two hospitals began to offer health insurance to groups of employees. Enter the advent of third-party payers.

— Franklin Roosevelt tried to include health insurance in the Social Security Act of 1935, but opposition by the AMA resulted in its being dropped.

— During World War II, employers began to offer health insurance coverage to compensate for wage controls placed on employers.

— Harry Truman proposed a national health care system, but again the AMA ostracized the plan calling it the S-word: “socialized medicine.”

— Second fundamental change: During Dwight Eisenhower’s presidency, a 1954 law allowed contributions made by both employers and employees for private health insurance to be tax-free. Millions more Americans were able to gain private health coverage through their employers.

— Third fundamental change: John Kennedy proposed universal coverage, but when his presidency was tragically cut short, Lyndon Johnson picked up the torch. He was unable to get universal care, but through tenacity and legislative mastery he achieved insurance for the elderly, the very poor and the disabled. It was 1965 and they called it Medicare and Medicaid. The AMA was vehemently opposed to the legislation, but Johnson seduced them by allowing them to price their own services and procedures. This is when health care costs dramatically and momentously increased.

— In 1973, Richard Nixon signed the Health Maintenance Organization Act to help reduce costs.

— In 1994, First Lady Hillary Clinton formed a reform task force, but nothing came of the valiant effort for a variety of reasons, not the least of which were the infamous “Thelma and Louise” television ads.

— Fourth fundamental change: On March 23, 2010, Barack Obama achieved near universal coverage with the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, insuring tens of millions more Americans. It was the first significant reform legislation in 45 years.

Fundamental change is inherently disruptive. Fury and acrimony ensued, meaning all hell broke loose, with the passage of Medicare and Medicaid. For example, at the time, hospitals were segregated, but to receive Medicare funds, hospitals would have to become integrated. Imagine how well that went over in the overtly racist South.

Fundamental change is inherently disruptive. Fury and acrimony ensued, meaning all hell broke loose, with the passage of Medicare and Medicaid. For example, at the time, hospitals were segregated, but to receive Medicare funds, hospitals would have to become integrated. Imagine how well that went over in the overtly racist South.

But now Medicare and Medicaid are popular and well-accepted programs. Don’t believe me? Ask any senior to give up his or her Medicare and watch the reaction. For me, Medicare is far better than any employer insurance I’ve ever had.

The ACA was another disruptive fundamental change. Indeed, seven years later we are still in the eye of the storm, even though more than 20 million Americans gained insurance. The ACA needs to be improved, not scrapped. Down the road, Obamacare will be as popular and well accepted as Medicare and Medicaid.

Before we can achieve universal coverage like all the other industrialized nations, we have to decide and demand — as a society — that health care is a right for everyone, not a privilege for some, and that providing universal coverage is a legitimate role of government. And the American Medical Association must be on board.

Until that happens, we’re doomed to futilely toil like Sisyphus. Once we all come together with a shared philosophy, that stone we push will stay atop the summit.

Austin, Texas

Austin, Texas