Emergency rooms, psychiatric facilities and geriatric units can be pressure cookers for patient-on-worker violence, with nurses bearing the brunt. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, an average of 17 RNs are killed while on duty each year. A new Texas law enhances the penalty for assaulting ER personnel to a felony. I wonder if it would have helped in the following case.

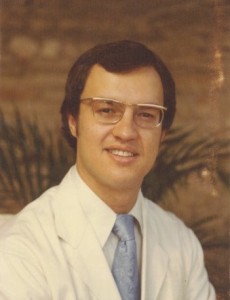

Registered nurse Steve Lulenski was two months shy of his 28th birthday when he was killed 37 years ago while working in the ER of then-named Brackenridge Hospital. The event shocked the sleepy Austin community.

On Feb. 4, 1976, Lulenski arrived on time for his 3-to-11 shift. Around 5 p.m., Sam Sanders, a 37-year-old from Manor, came to the ER demanding a penicillin shot. Lulenski agreed to admit him. Tom Forest, an orderly and friend of Lulenski, began taking his vital signs, equipped with one of the hospital’s new digital thermometers.

Sanders said he wanted a real thermometer and began shouting profanity. He said the thermometer was a mind-control device and that they were using him as a guinea pig. Hearing the commotion, Lulenski entered the room and told Sanders that if he didn’t calm down he would have to leave.

Sanders left, went to his 1959 Chevrolet pickup and retrieved his shiny 20-gauge shotgun. Focused and walking fast, he returned to the ER. Workers dived for cover. A clerk grabbed a baby and ran. Police officer Greg D’Amore was dealing with an intoxicated patient when a lab tech frantically told him, “There’s a man with a gun!”

Lulenski saw Sanders in the doorway to his room and said, “What are you doing back in here? My God, get out of here!” He threw a chair toward the gun, then turned to escape from another door when Sanders raised his 20-gauge shotgun, took aim and fired once, hitting Lulenski in the back below his left shoulder. The blast penetrated his aorta and pulmonary vein, killing him instantly.

D’Amore turned around just in time to see Sanders fire, then point the gun in Forest’s face. D’Amore bent his knees, raised his arms and fired his service revolver three times, wounding Sanders in the arm, leg and side. To this day, D’Amore is moved that the hospital staff rushed to save Sanders the same as Lulenski. “To them, he was a patient who needed their help.”

During Sanders’ trial, testimony revealed he killed his uncle with a shotgun in 1971. Diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, he was ruled innocent by reason of insanity and committed to Rusk State Hospital. He was discharged in 1974, taking his meds. He was doing well — enrolled at Austin Community College with a B+ average and working a janitorial job.

His mother told the court that he stopped taking his meds because they constipated him. Things went south from there. He dropped out of school and boarded up the windows to the small house he occupied behind his mother’s home. She told the court that she didn’t understand her son. He dug a large hole in the front yard and put a jar of water in it. When she knocked on his door, to ask him about it, he slammed the door in her face.

Psychiatrist Richard Coons crumbled the insanity defense of attorneys Laird Palmer and Rip Collin by testifying that Sanders told him he knew what he did was wrong. The jury convicted him, and Judge Tom Blackwell sentenced him to life in prison. Nine months later, an inmate smashed Sanders in the head with a lead pipe, killing him.

Since this tragic case, safety improvements have been made. But we’re not there yet. Statewide, we need improved community mental health care. And we need intensive mental health training for police, health care workers and judges. Mental health first aid for the general public should be universally accessible.

The new teaching hospital to replace University Medical Center Brackenridge will have a strong focus on psychiatric care. Long overdue, it will be a welcome resource for the community. A plaque honoring Lulenski’s memory still hangs in the Brackenridge ER. You can bet it will make it over to the new hospital.

Austin, Texas

Austin, Texas