[This commentary was also published in the Austin American-Statesman, the Atlanta Journal & Constitution and the Houston Chronicle.]

Barbara Jordan’s candle burned out in January of 1996. It was too early; she was not finished. Her ghost haunts me constantly these days. In the spring of 1992, I took a graduate seminar from the former Congresswoman at the LBJ School of Public Affairs in Austin. The presidential primaries were taking place.

In a rare digression from discussion of high governmental principles, we would briefly touch on the primary candidates. One of my classmates favored Tom Harkin, some Paul Tsongas, and another California’s explosive Jerry Brown. Professor Jordan respected them all, and in a rare peek at her own view, she opined that the governor from Arkansas seemed the most presidential, the most capable of leading the nation. Moreover, she regarded his wife, Hillary, as caring and capable, fitting for a first lady.

At that time, Gov. Ann Richards had tapped Jordan to serve as Ethics czar for state government. Shortly after Professor Jordan’s gatekeeper/secretary rolled her into class one January day, the professor announced that she had gotten a call the night before from Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton. The Gennifer Flowers story had broken the day before, and Gov. Clinton sought Barbara Jordan’s advice on whether to proceed.

She told us that she advised the governor that those matters were private, that the American people had the ability to distinguish between actions that were personal and those that affected the national interest. She advised him to level with the American people, and in her deliberative, authoritative voice that invariably sent shivers down my spine, she told him unequivocally, “You must press forward.” It was that simple. The rest is history.

I learned a lot in Professor Jordan’s class. I absorbed her conviction that public service is a high and honorable calling. I learned that the Constitution of the United States is a purposely vague and sacred document, that it forged a government in which our liberty was not entrusted to a particular branch, that one branch would check the others. Above all, I learned that in our great American experiment in democracy the people hold the power, and rightly so.

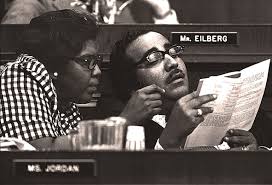

Barbara Jordan served on the Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives when considering the impeachment of President Richard Nixon in 1974. On July 25, Congresswoman Jordan made a riveting 15-minute speech that effectively focused the nation. Two weeks later, the president resigned.

[To view that speech, click here.]

In her speech, Congresswoman Jordan proclaimed, “My faith in the Constitution is whole, it is complete, it is total. I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction of the Constitution.” Later in the speech, “Impeachment must proceed within the confines of the constitutional term, ‘high crimes and misdemeanors.’” And later, “Common sense would be revolted if we engaged upon this process for petty reasons. Congress has a lot to do…. Pettiness cannot be allowed to stand in the face of such overwhelming problems.”

I would not presume to speak for Barbara Jordan posthumously. But I can’t help wondering what she would think of publicly examining presidential sexual indiscretions under a microscope, when in her day high policy was often made at night by powerful white men in smoke-filled rooms with plenty of alcohol, women, and playing cards. She, of course, was not invited. The press was invited, but such conduct was not news. Reporters turned their heads away from unseemly behavior.

This I know. If Barbara Jordan were here today, what would disturb her the most about this imbroglio is the resultant tipping of the delicate balance established in the Constitution among the branches of government. Federal Court (judicial branch) decisions allowing the nation’s highest officer to be sued and allowing those closest around him to testify against him have effectively weakened the presidency (executive branch). And I know she would be alarmed that the power of the recently established Office of the Independent Counsel has been allowed to escalate unchecked.

I think Professor Jordan would smile knowing that the fate of the remaining two years of the Clinton presidency is left in the hands of the people. Her faith in the American people’s careful, deliberative and fair judgment was whole, complete and total. As she told Gov. Clinton, she believed in the people’s ability to distinguish between actions that were personal and those that affected the national interest. She would remind us again that impeachment is solemn and must be reserved for treason, bribes, high crimes and misdemeanors, not petty offenses.

She would tell the House Judiciary committee to embark on a course of action that would cleanse, not pollute the body politic, that would strengthen, not divide a weary nation and leave us more cynical. If we could ask her now, “What should we do as a nation?” She would tell us authoritatively, like she told the promising governor from Arkansas in 1992, “You must press forward.”

Austin, Texas

Austin, Texas